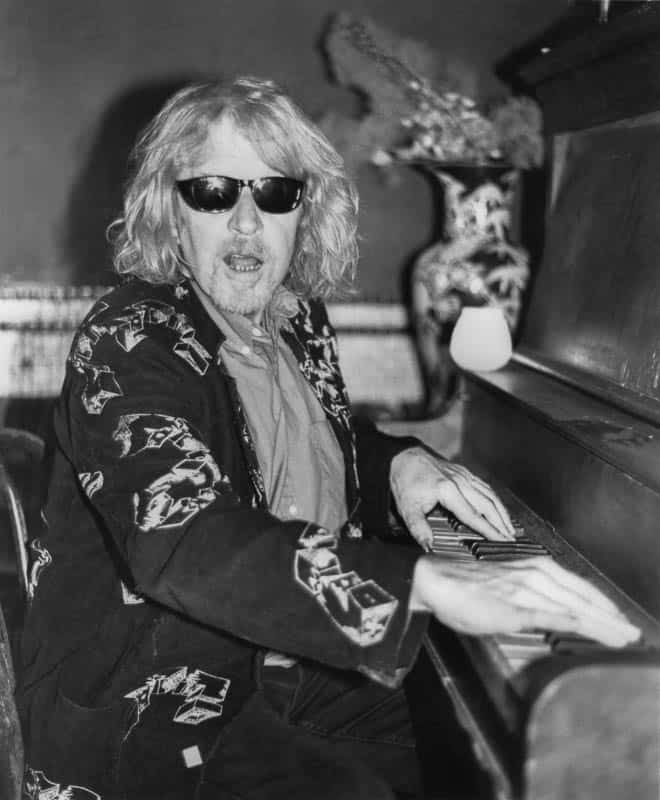

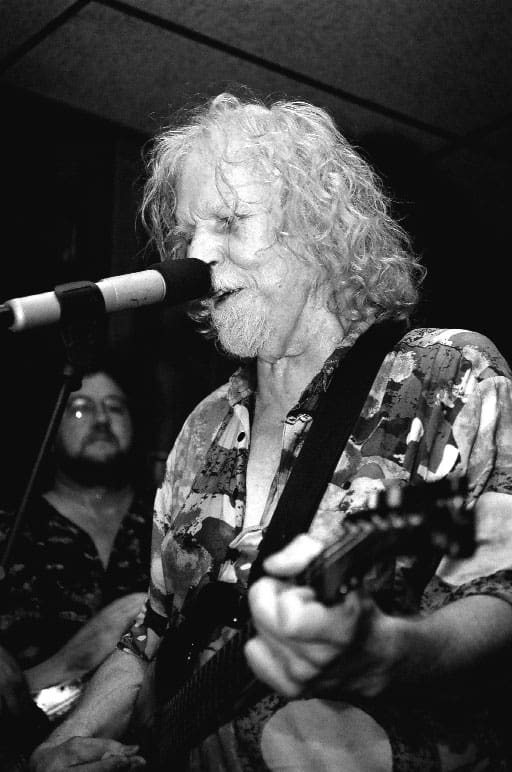

Willie Murphy: The sacred art of making people dance

A conversation with Willie Murphy

For more than 30 years Willie Murphy has been fashioning a blues and R&B legacy in the Twin Cities and beyond. He produced Bonnie Raitt’s first album (which featured contributions from him and his band, the Bees, as well as from Spider John Koerner). And his 1969 collaboration with Koerner, Running Jumping Standing Still, is widely acclaimed as a psychedelic/folk/ blues classic. Throughout the ’70s and the ’80s, Willie and the Bees defined live R&B music in the Twin Cities with their category-defying mix of blues, R&B, jazz, funk, reggae, and rock. He has toured widely, including performances throughout North America, and in Italy, France, New Zealand, and Turkey.

In 1990, the Minnesota Music Academy enshrined Murphy as one of the three charter members (with Bob Dylan and Prince) of the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame.

Since the late ’90s until it closed in August 2006, Murphy performed weekly at the Viking Bar with numerous musician friends, including longtime keyboardist and original Bee, John Beach, and other guest Bees. Murphy has been performing for the past 15 years with his band, the Angel Headed Hipsters, at Whiskey Junction, Minnesota Music Cafe, Famous Dave’s BBQ and parties.

Murphy has also produced several CDs, including Koerner’s StarGeezer and other musicians such as Gene LaFond, Becky Thompson, and All Around Woman by Suzanne Warmanen, which was playing during our mid-November 2004, conversation at his beautiful home in the Phillips neighborhood of South Minneapolis.

I understand that you are a voracious reader. Tell me about books that have influenced you.

I really like modern stuff, there are some European writers I really like: Raymond Queneau, George Perec. And Joseph Roth, of course. I’ve read everything he’s ever done, been translated. He’s one of the real geniuses of the modern era. He was Austrian. He died in ’41, I think. He writes about the end of the Austrian Empire, about the displacement of people and soldiers after the World War and the Jewish communities and the shtetl. He’s really incisive and very poetic. Just stunningly beautiful writing! He’s considered one of the great 20th century masters.

We were in Paris once, and I and my girlfriend, Elka, happened to have a book of two novels, Legend of the Holy Drinker and Right and Left, that we’d brought along and were reading. One day it was raining, and we were in the Jardin Luxembourg. We went into the first bar across the street and there was a big plaque on the front of the building: “This is where Joseph Roth lived, and wrote his last novel”—one we had on our trip. He lived on the top floor, and in the book there was this description of him living in this little place above this little brasserie and coming down the steps every day and starting to drink at the bar and writing . . . he kind of held court there, was very famous among certain circles. That was really a great experience.

I want to ask about cinema, films influencing your music, also literature.

I read like crazy. I don’t know how I could say how either one influences me, but they influence your whole life, you know. Great works of art can really turn you around. I write a lot of those songs that people don’t understand and some of them are influenced by things I read and think about.

I get that when I hear your songs . . . they seem inspired by poetry, philosophies.

I don’t think so directly, although this one song I wrote was a response to this book that I actually didn’t read, but I read many reviews of—I read London Review, and New York Review and things like that. Francis Fukuyama was a right-wing shill. The End of History was anti-everything that happened in the ’60s, everything progressive, saying “that’s all over.” I had a song on Monkey in the Zoo about that called “Open Letter to a Politician” inspired by that. I write a lot of political stuff, not directly inspired by my reading, but by life.

I loved a line you sang during “Cry to Me”: “The world’s growing more overpopulated and yet we’re growing more lonely.” I think that’s profound.

I’ve been saying that for years . . . it’s true, of course. For a long time I was on a kick about post-modernity, and then we moved beyond that and are in this stage—“post-life,” I call it. (Laughs) There’s so little real life going on. It’s all about telephones, television, computers, and cars, at least here in this country, and so-called information! There’s more suffering in the world now than there’s ever been. That’s the bottom line. It’s hard to do anything politically active nowadays that seems effective. But we’ve got to keep finding new ways to do it.

What do you feel are the most effective ways of doing it?

I’m a very independent guy, and I’ve rejected the Los Angeles music biz and stuff—I did have a big shot at it once, to be a producer for a big label, which I turned down. But I can make records, write songs, and do music that seems real to me. I don’t see anything wrong with writing political songs . . . there’s a cliché out there that says that that’s boring, but it doesn’t have to be. You can do things on a very personal level, in your own life, against the system. It’s small but it means a lot to you personally . . . for instance, I don’t watch television. I don’t eat meat. You have to constantly compromise, of course, to survive at all. There’s a lot of stuff going on on the Internet that shows how you can become involved politically.

You’re also a legendary cineaste. What films have influenced you?

I was going to cite one movie, on how a movie can change your life. When I first saw Andrei Rublev by [Russian filmmaker Andrei] Tarkovsky, I’d been fighting alcoholism and drug stuff. But I had quit drinking for about three or four years. I saw that movie, and I went out and got roaring drunk. And then I went back and saw it the next night again. And I came away with a whole different idea. The first night I saw it, it made me despair, and then when I saw it the next night, it gave me hope. It’s about the human condition in life. But I think what gave me hope was the beauty of the art that it was. It was the most advanced, beautiful piece of work I’d seen in my life. And it still is in my top five—and I see a lot of films!

You have a top-five list out of all the films you’ve seen?!

Well, it’s hard to pick a top five. I used to say it was my favorite, but I always think I’d put it in my top five.

Sight and Sound magazine every 10 years has a huge poll of critics and directors from all over the world rate their favorite films. Andrei Rublev keeps moving up the list. Tarkovsky just shook everybody up. Some of his stuff seems dated because it has that sensibility of the ’60s. But the realness of it is still there, the values of it are still really important. And he always asks the big questions. They’re more important now than ever: “What is life?” “What’s it all about?” “What are we doing here?”

What would you say the other top-five films are?

Well, I never really say that. I just know Andrei Rublev by Tarkovsky would be one of them. (Laughs) What I like to do instead of picking films, is picking somebody’s whole ouvre, like Fellini’s group. Renoir, more [films] than I could ever name would be in the top five.

I love La Strada, and I love La Dolce Vita. French films in the last 10 years or so have been incredible. Then of course, the Iranians, [Abbas] Kiarostami, the Chinese. I think Kiarostami’s film Through the Olive Trees might go into my top five.

What drives you to keep performing? What drives your music?

That’s about the only thing that I know how to do. (Laughs) I mean, I couldn’t get a job to save my life if I had to now. I will say, when I was about 18 or 20 I had observed enough to realize giving your life away to “The Man,” as I would call him, doing something all your life that didn’t really have anything to do with you or living, was not a thing I wanted to do. It was fortunate that I started to find out I could make money by playing music. I’m my own boss and there’s, of course, tons of compromise; I’m certainly not doing all the music I would like to do. But, I manage to keep doing it and make records once in a while. Of course, nobody buys them because it’s small independent stuff. But I have enough fans here and there and in Europe and places, that makes me happy.

It’s a good life, as opposed to selling to the larger music corporations.

Oh yeah! And you learn to live within your means—like I can smoke these nice cigars and I can travel to Europe once in a while. People think I have a lot of money . . . I’m way below poverty level. But I live here in Phillips. I found this beautiful house; I’m very fortunate. I don’t drink anymore or do drugs, which I did for years. That saves me a lot of money. So, it’s a matter of choices. Not everybody is as fortunate as I am, being able to play music and enjoying it, you know.

You started playing music for a living when?

Probably around 20. I’d played in a few little bands through my teenage years. One of the two or three regular jobs I had was at the post office, when I was in my early 20s. When you first work at the post office you have a certain amount of freedom to punch out whenever you want to without people knowing. At that time I was playing in bands. I tried to do both. At one point they caught me and fired me, but they also tried to fire me for having long hair, but the union stood up for me in ’63 or ’64. I wasn’t even in the union. That’s the last time I think I ever had a regular job.

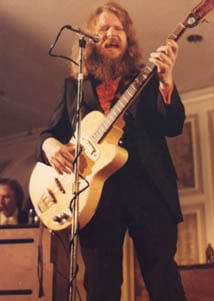

I played in a lot of R&B bands—Dave Brady and the Stars was a big one, a group called the Nobles, which had been called the Big M’s, was one of the quite notorious bands. And then somehow I hooked up with John Koerner and we did a thing from about 1965 to 1971—we toured the country, recorded for Elektra records.

That was Running Jumping Standing Still. How did the touring go?

We’d just jump on a plane and head out to New York or Boston, Atlanta, or drive sometimes. We were in San Francisco, I remember in ’67, the Summer of Love. We could’ve kept doing it—they wanted us to make another album, but Koerner decided he wanted to do something else.

I thought, “Well, I’d really like to get back into R&B stuff. So I came back here and started Willie and the Bees. That’s when they offered me the big producer job and I turned that down. I didn’t want to move to L.A. or New York, and that’s the choice they gave me. Warner, Elektra, Atlantic . . . I did have a maybe somewhat naïve idea you could be successful in the locality that you chose, in terms of the business of making records and stuff. It never really turned out that way. But you know, I’m happy. You learn to do things yourself, you become pretty self-reliant.

So, do you produce your own albums with your studio here?

Oh yeah, I produce my own and many others. The studio here has been slowly growing. This project here [Suzanne Warmanen’s All Around Woman] is the first one where I brought in the band and recorded a whole band live. My solo piano, the last one was done here. I do jingles, and film music, and a lot of stuff by myself. I’ve just gotten to the point where I can record a large group live.

Tell me a little more about your experience with the Bees or what inspired you to play R&B.

I just grew up in South Minneapolis and went to grade school at St. Stephen’s on Fourth Avenue, before the freeway was there. It’s kind of a black neighborhood, and I knew a lot of the kids from around there, and we’d just listen to Little Richard, Fats Domino, that kind of stuff.

One of the kids’ parents drank a lot, but they gave him a lot of money, and every Saturday we’d go downtown and check out what R&B records came into this little store called Musicland, which was just a tiny little store and now is an empire. They had all the R&B stuff that wasn’t on the radio around here. I remember when I first heard Little Richard, I just played that record over and over again. I started buying records.

I just continued like that. I went to Central High. . . it was the music that I loved, still do! Blues, jazz, I’ve got a huge record collection upstairs. The house was really nice—when I saw all these shelves and track lights upstairs I thought, “This is for my record collection!”

I think as far as pop music goes, artistically, the African-American thing is the biggest thing that ever happened in America and, in a way, in the world. It’s real culture, you know, not just pop music. It affects all of culture to a great extent.

How did you find the Bees?

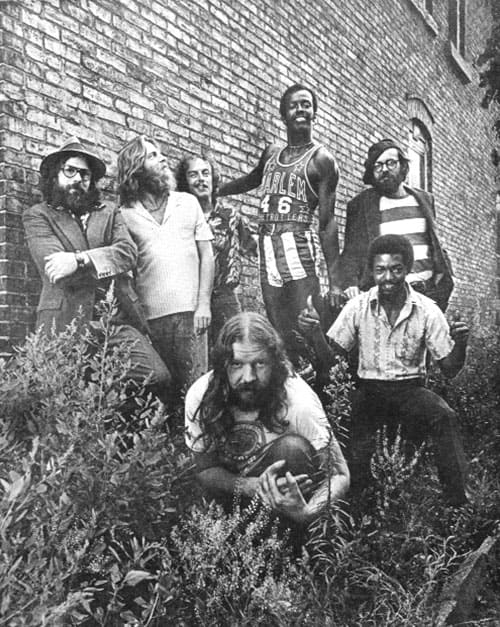

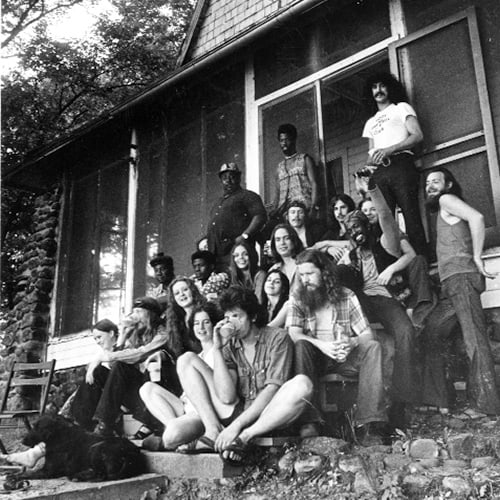

Well, I’d had much experience playing R&B. When I was with Koerner, we did the folk thing, and that was nice. But I’d always had a hankering to start a big band. I’d played in a few big bands with horns and four singers up front and stuff like that here. So I came back and called some people that I’d worked with, like John Beach, horn players I knew, and whatnot.

Back then it was easier to have a band. It’s harder now, because there’s not enough money. A lot of musicians that are any good are playing in four or five bands, which means that all of the bands have the same repertoire (laughs) and nobody gets time to rehearse much. But it’s really hard when you become an adult, especially now with the postmodern constraints on time and money.

Musicians’ wages have gone down steadily since the mid-1970s. It really is bad now. I love playing with a band; I’m a band kind of a guy really! It’s my thing. I really love big bands, I like arrangements, I like writing for it. I love making people dance! To me, that’s almost sacred, that I can bring an experience to people that gets them away from the phony reality in their lives, the dissonance in real time. But, lately, I haven’t pursued working in the clubs much because it’s too little money. I can make more than I do, but I can’t break my back hauling equipment down there for $50 to $100. I want a large band with horns and several people singing; it’s really impossible, you know.

How many people were in your band?

Well, Willie and the Bees had between eight and 12. I don’t remember exactly how many we had when we played [the Triangle]. There, the front door man carried a can of mace and would spray it whenever he had a little trouble. He’d get scared and pull his mace out. The mace would be in the air and so we would be playing while we had tears in our eyes and were sick to our stomachs.

We played at the People’s Center, Dania Hall, and the Firehouse, which is now the Mixed Blood Theatre. There were three bars, called Mike’s, Jim’s, and Bob’s that were on three corners of an intersection, of Sixth and, I think, 17th. It’s a funny street. We used to call it the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It was a way between the West Bank and Phillips at night. You can’t use it now because they built that depot for the light rail, you know. Willie and the Bees used to rent the bars and put on big dances.

One time I went sideways and nearly fell off the stage at the Joint next to the kitchen. I grabbed the plasterboard wall next to the kitchen. I was hanging on, the guitar hanging from my neck. John Beach was trying to pull me up and he couldn’t at all, and we both started laughing and I nearly fell again. The band kept playing the entire time.

Back then it was so crowded that stages were put up in the air to make more room. We used to play the River Serpent in St. Paul on Navy Island. Once, someone got shocked and it knocked him back against the wall.

One time, late ’70s, I think it was ’78, at the River Serpent, there was a huge fight, the biggest brawl I’ve ever seen. There were nearly a couple hundred people all fighting. We were playing “On the Wings of Love” by John Beach! It wasn’t a peaceful, loving gathering. We, the band, were hiding behind the speakers. People with injuries and bloody from fighting would come back where we were and hide.

The Music Bar was our band space. It was located next to Global Village where the Dollar Store is now. The Bees would rehearse there, and we’d have jam sessions and rent parties there. Many people came and played there.

I remember before the high-rises there was funky, bohemian housing. That was all taken down. Many houses were torn down in the late ’80s.

The West Bank is the most cosmopolitan place in Minneapolis. I love that about it, and that it’s still international. There are African Americans, Asians, Middle Eastern, Hispanics. The Korea House [was] a great place to eat and watch people out the large window. The Riverside Cafe was a great people-watching place. They had great food. It was like a headquarters for people on the West Bank. While the Bees would be rehearsing at the Music Bar, I’d go over to the Riverside Cafe and write horn sections and songs over a cup of coffee. Then I’d go back with the work. It was great then. It’s not like that anymore. Developers have been trying to get rid of the bohemians and beatniks for a long time.

The Triangle Bar was a wonderful place. It was legendary! It was this wild place where all the beatniks hung out. Everywhere Koerner and I went when we were touring Running Jumping Standing Still people asked about the Triangle. I think it had the oldest liquor license in Minneapolis, until they closed it down.

At first in the early ’60s everyone hung out at the Mixers Bar a lot. People were getting of an age to drink, and came over from Dinkytown. It was first Beatnik scene. That was really fun! Then the scene moved to the Triangle Bar, which began having live music. That got so crowded that we’d go over to the Viking, where there were only about seven older Scandinavians. Then it became a youthful crowd. Then we moved over to the 400 Bar, then 5 Corners, then Palmer’s where the older people hung out. Each one would change from an older to a younger crowd. That’s happening now. We went into 5 Corners, the last place for the old people—they were getting drunk and playing and dancing to polka music.

I see kids hang out now, like the hippies used to. They hate being called that, but they’re like we were then. We were thought of as hippies but hated being called that. We all had tattoos and earrings. Somebody would stick a safety pin in their ear one night and call it an earring. I had three or four of them in my ear back in the ’60s.

Bill Hinkley mentioned you’re excellent at “workshopping,” doing the arrangements that make people like your music.

I’m a good arranger because my musical listening and kind of the music where I live is quite varied. I love jazz and I love R&B—from folk to funk and beyond is all one music in so far as American music goes. I’ve never felt there were any real constraints about mixing all the things I hear—my horn arrangements, for example—without being totally conscious of it, of course. I imagine people like Charles Mingus, James Brown, and Wilson Pickett play a large part in how I like to write horns. Rhythm is my middle name. I write a song the way I hear it. I don’t think, “This is going to have an African influence” but later think, “Boy, that’s something like Fela would’ve done!”—who was heavily influenced by James Brown! I don’t consciously do anything like that. I like variety, and I like my music to have everything in it, if I can. I want people to dance, I want them to appreciate the musicality of it, whether it’s the singing, the melody, the horns or the harmony . . . I like all those elements in there. I like good words. Not necessarily totally serious all of the time, but worthy of your attention.

As a listener, that’s what compels me: Besides all of those elements you’ve mentioned, also the good words.

In pop music when I grew up, there were songs we as musicians referred to as “rhythm songs,” which means that the important thing is the rhythm and the dancing, more than the words. You can write a good rhythmic dance song with good protest lyrics or serious lyrics over it, but generally it’s weighted one way or the other. Most of the singer/songwriters—we used to call them “folkies”—are way too self-indulgent and they don’t have the background to know what poetry is.

Writing songs isn’t necessarily writing poetry, but you should understand what words can be. I think you have to strike a balance. Some of the lyrics I think are the best that I’ve ever written, people pay very little attention to. They’re more interested in the rhythm, and vice versa sometimes. I think music is important. I don’t think you should just pick up a guitar because you know three chords. You should go back to the woodshed and learn more about music.

Tell me more about what you see as the importance of music.

I don’t think music really changes the world. But it can change how you feel from time to time, and that way it’s been used to manipulate people. I can’t stand that everywhere you go now you hear music. I don’t read a book and listen to music at the same time. It should be good enough to take your whole attention. Theodor Adorno, one of the great Marxist theorists, wrote a lot of good stuff about how capitalism changed music from what it once was—from a sacral society when they had weddings and dances and music for special occasions. Now I think young people use music as an identifying badge of their particular group, culture, and a lot of the young people listen to only one kind of music—older people too.

The worst thing about it is that it works as a hypnotic, I think. It prevents you from getting out in the street and fighting the system. But music can be very relaxing, to do yourself especially. It’s wonderful. When I come home from a gig, what I usually do is sit and play the piano or guitar or put on some old jazz records and really listen to them and appreciate them. I think music has the importance of being deep spiritual-related, or it can. Pop music is a whole ’nother thing, the world is inundated with it.

When I was a kid I probably had the stereo on 20 hours a day, listened to Coltrane and Mingus and B.B. King and Wilson Pickett. But now I only really play it when I really want to hear some music. I hate walking into restaurants and hearing more music. It’s so pervasive, really.

For example, I wish KFAI would not have all those blues programs and reggae programs. I like that, but I think we should be more discriminating. I like some blues and I like R&B, but they should have a show where they play all that stuff, plus some Iranian music and some classical music . . . It should be one huge radio station all of the time! I was a broadcaster for KFAI for eight years. I was there when it began in 1978. I hosted the first R&B show, and got Lazy Bill Lucas his show. Now so many blues shows have cropped up—too many, I feel.

It kind of cheapens it?

It really cheapens it, in every sense of the word. People get it all over the Internet for free. As a musician, I have that complaint—it’s my livelihood, it’s dwindling. They’ve really wrecked it, like they’ve wrecked everything else. Capitalism! Write that down! I still know it’s going to all go down one of these days, with bozos like Bush.

You have to realize—well, I do anyway and I’m 60 years old—that people have grown up with this phony culture that we’re talking about. They think that’s reality. I don’t want to go back to the past and all that stuff, but all this inundation of phony information, computers, cars, television . . . a lot of people, that’s all they know.

You miss out on a lot of real experiences.

Not only that, but it’s hard to experience a lot of real experiences anymore, because we’re inundated by this. It’s hard to fight, because we’re buried by this phony culture. One of the things I’d read years ago that struck me hard was Frederick Jameson’s seminal piece on postmodernism, Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capital. He explicitly challenges artists to find ways to answer this inundating phony cultural influence, because the old ways don’t work anymore. So I keep that in mind a lot.

A lot of the people are addicted to television; they’ll watch six or seven hours a day at least. People don’t have time to get informed! There’s people out there that can inform you, but you have to be proactive about it. I think it’s important to make some decisions about your personal life. A lot of people just go along and get by. I think, for example, about not eating meat. A guy from The Nation, I think it’s Eric Alterman, wrote a big thing about not eating meat, but then he wrote, “I’ll still go to McDonald’s, because I really like it.” If you know it’s not good, if you even just suspect animals are maltreated, you should do something.

You can write letters to editors. I think it’s important to talk to people—not just your own people—but go out to your relatives that might have voted for Bush and try to talk to them. Unfortunately we’re so polarized now that we end up only associating with our own kind, people that share our beliefs.

Your travels—France, Italy, New Zealand, Belgium, the Netherlands, West Germany—what is the response like from audiences from those places as opposed to here? Is it very different, the music culture?

[Classical guitarist Andres] Segovia said that you have to leave your hometown, or people get sick of you. I understand that. When I play in Italy, I get a lot more respect. I get plenty of respect here. But people really pay attention over there. I have a song called “Keep on Rockin’ the Boat” that’s very political. I wrote it in about ’90-something, but unfortunately it’s more prescient now than ever. It’s about people who keep fighting the system, people who keep being activists. It’s a thank-you to them. And maybe an inspiration, if possible. I would play that over in Italy, and with my little Italian, I would explain the lyrics. Every time without fail, people would stand up and cheer when I said that! I think even without really knowing it, when they hear somebody that’s real—lot of these so-called blues acts are just sort of copying records and such—they do appreciate it.

Do you like Italy for the place, the music, or the . . . .

Everything. The food . . . it’s really nice just to get out of here. I have a really good band in Italy. The core is five pieces: a really good sax player, a really good guitar player, a good bass player, then me and the drummer.

Do you have any recordings from these sessions?

No, but actually we started a project with me and the sax player. He’s really phenomenal to play duets with and sing jazz standards and stuff. He got so excited about it that he got us some time in a recording studio. He came to the house I was staying at one day and said, “Come on! We’re going to the studio to record this.“ I wasn’t prepared. We played a bunch of stuff; he thinks it’s good, but I don’t think it’s quite good enough to use. But we’re going to continue that project when I go back.

What about France?

I love France, I love Paris. It’s really pricey, but it’s very fun! I like the Mediterranean; it’s very warm, the people are very warm. Italian people are very nice. The only people I’ve ever met that, as a whole, were even nicer if possible than the Italians were the Turks. Turkey is incredible. But in Italy I have this established thing, I play there a lot. Have some good friends there. It’s really beautiful. It’s really nice there during the summer. We play a lot of festivals, outdoor gigs. It’s a blast.

You play with Turkish musicians?

A little bit . . . the guy I play with is a virtuoso. His name is Erkan Ogür—he’s very popular there. When I was last there, his newest CD was number one on the charts. He’s credited with bringing back all this old Anatolian folk music. His records are mesmerizing and beautiful! He plays guitars with no frets, with real low action and seven or eight or 10 strings—he’s modified them. He also plays the saz, which is a traditional Turkish string instrument. I didn’t go there to play, but my friend Robert One Man Johnson hooked me up a gig. We played in a fancy club in downtown Istanbul. It was packed. Erkan played guitar, and my friend Robert played and sang a little. Erkan is a virtuoso, and I caught myself leaning over to him and saying, “Quit noodling while I’m trying to sing! Quit noodling so much!” (Laughs)

When I was out in the provinces, there was this little weird town, Bergama, where the ancient city of Pergamon was, and they have some really incredible ancient ruins there. I went to a shop one day and heard this exotic beautiful Turkish music. I went over and asked, “What is that?” and the guy said, “That’s so and so’s style.” We were listening, and I wanted it and he said, “That’s my son’s band.”

When you walk in these places in Turkey, the first thing they do is give you tea. We’re drinking the tea, and he says, “Yeah, he’s going to be here pretty soon.” Pretty soon the son came and we talked a little. He understood I was a blues musician. He got all excited and said, “Come with me,” and we walked two doors down the road, just this little dingy town, funky, beautiful, old. He’s got this little place with all these speakers and musical instruments and electric keyboards, and he said “play the piano!” He turns it on and I start playing, and he listened—he was amazed. And then two of these guys from his band came in. And they were all like, “Wow!”

I said, “Play something of yours.” He pushed a button on the keyboard and it started playing this drum machine in 9/8 time. He starts playing and singing—it was just incredible! He said, “No, you play some more!”

I had an idea to get them all involved and started playing that song, “The Way You Do the Things You Do.” I was trying to get them to clap and sing a little back up; “doo wop, oooh, doo wop!” They couldn’t clap in 4/4 time like that. They kept getting off! It was really odd, and in these strange time signatures. I think for them it’s like being thrown in the ocean. It’s too free. There isn’t enough structure for them, you know. But that was really fun. We’d get all screwed up and then we’d laugh and laugh and try it again!

That’s cool. You don’t think about the timing being difficult in another place.

The first time you go to Europe you realize one of the real cultural strains in America is the African-American thing. Anybody here can go in the shower and sing Aretha Franklin. Even if they’re a terrible singer, they have some kind of idea of the feeling. Over there it’s totally foreign to them, pun unintended, and even more so other places.

I happen to believe—and I listen to a lot of that stuff—that American rhythm and blues from the South is the most exotic music there is rhythmically. I’m talking about funky exotic—the singing and combinations of rhythms that are just standard now. The combination of the slave field stuff and the gospel stuff, the Western things and the Appalachian English-Irish folk things, has really put some funk in that music, so that even now, some esoteric band in some little town in Louisiana is going to be like something you’ve never heard before.

Do any songs or singers stand out to you as major influences?

There are major influences, singers of R&B. Interestingly, three of the great singers that I love all come from the same town, Macon, Georgia. Little Richard, who was a great hero and influence on the next two, which are Otis Redding and James Brown. I think Wilson Pickett is one of the greatest singers of R&B of all time. I love Etta Jones, a great jazz singer. I think Louis Armstrong is one of the great singers of all time. l really love James Carr, Clarence Carter, all that soul singing, that’s my thing now. I love that. Little Willie John was a great one that I really loved. They all influenced me. I think Little Richard is my biggest influence. Ray Charles, and all the great jazz, of course.

Did you teach yourself piano and guitar?

My mother started me on piano when I was 4 years old. We didn’t have much money, but she loved to go to rummage sales, house sales, and buy stuff and collect. One day, she brought me a guitar, so I got a little book and I could play by myself. I had my first lesson last year with Dean Magraw. He’s really brilliant. One lesson has lasted me this long. He showed me ways of playing chords that I already played but different ways to play them, different fingerings and things.

I’d said a while ago that I’m real self-reliant; I’ve always been that way. But I realized a while ago that having teachers can save an awful lot of time. But my mother started me on piano when I was a kid, and then when I was going to Catholic school it was the nuns through eighth grade. Then I started playing like Little Richard and Fats Domino and Jerry Lee Lewis.

That’s the other thing about media now in our day and age. All of our heroes are on records and in pictures: Marlon Brando, Wilson Pickett, and Jack Kerouac, were people that influenced me. I didn’t have a father when I was growing up, so you have to realize that everything that I talk about, when I grew up influences weren’t always that real, either.

I’d read on your website you were able to play with people like Son House and Mama Thornton. Did you work with them directly?

No, I met Son House a couple times because when I produced Bonnie Raitt’s first album—she was a fan of me and John Koerner’s, you know—we played in Boston a lot, and she was going to Radcliffe then. Her manager was the manager of Son House. I met Son that way, and also when we played at the Newport Folk Festival.

I played directly with Sleepy John Estes and Brownie McGhee and a lot of those people back then. I encountered Mama Thornton several times over the years. I don’t think we actually played music together, but we hung out and drank together a few times. I and my band backed Dr. John up whenever he came through town for a while! We’d hang out afterwards and sing and play. He would tell stories about New Orleans. And my band has opened for Muddy Waters and James Brown, people like that, a lot. And played the same shows with them.

Back in the old days, Koerner and I used to have really memorable gigs because of the backstage antics—people like Jefferson Airplane, the Byrds, Van Morrison, all of those kind of people, Janis Joplin. Those were the days! Little did we know how it could change.

I enjoy being angry at the world. If you can cultivate that, that helps! (Laughs) There’s so little else that you can appreciate in this culture. Yes, you can make it a point to go out and walk. I walk the dog and I really love it, and I go out by the lakes and the woods and the rivers. Justice is a strong motivator. Fighting for justice, and feeling righteous about it is enjoyable.

Another book you should mention that I think people should read is by David Harvey: The Condition of Postmodernity. When I wrote some songs on my album in ’97, ’96, ’95 which, like I say, unfortunately addresses current events more now than it even did then, I used the word globalism, and corporate globalism. These are terms that weren’t in common usage then; they are now! But they came out of reading a lot of postmodern theory; I’ve read a lot of Marxist theory.

I think it’s important to disseminate these ideas to people. A lot of people know that the world is really weird, but they don’t know why and what’s going on. It’s easier to understand now than it was 10 years ago. But this has been happening from about ’73, you know. That David Harvey book is great, because he talks about the end of Fordism and the beginning of flexible mode of accumulation, the capital enterprise, and stuff. It’s all about outsourcing, fragmentation, and buying other companies and selling each other. Basically, it’s about the fact that when capitalism went into crisis in the early ’70s and OPEC was formed, the way they answered it was to do everything they were doing, only a lot harder and a lot meaner, instead of backing up and becoming compassionate.

Is there something you’d like to say about your hopes for the future?

My first thing that comes to mind is we kick these crooks out and that America wakes up. I hope that something happens that would prevent people watching television. It’s hard not to think of those kinds of things now.

I never sought fame and fortune, but I’d like to have a little more acceptance of my music, maybe live a little more comfortably as I get older, you know. That’s not a great hope, but that’s a constant nagging thought. But on the other hand, I’m reasonably happy. All I need is a little more money.