Willie and the Bees · Honey from the Bee

Excerpt from Hijinx and Hearsay: Scenester Stories from Minnesota’s Pop Life, text by Martin Keller, photographs by Greg Helgeson. Reproduced with permission from the Minnesota Historical Society Press © 2019. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher.

On the best nights at the Triangle Bar-when oxygen and elbow room were scarce and a tall black man dressed in a Harlem Globetrotter’s uniform played his big sax while walking atop the length of the bar where patrons drank and bopped in place-you could feel like there was no better place to be. As the rest of the band wailed, shoved into an impossible angle inside a tight corner, their funky originals, R&B covers, and rock ‘n’ roll blasts made you believe you had achieved something like a West Bank nirvana. Only the occasional soulful ballad would slow the spinning rotation of the Triangle so that it would not fly off into space.

No matter where Willie and the Bees played, there were no strangers, only a fan hive. The band’s West Bank shows in the late seventies, while the hippie enclave was still entrenched there at Cedar-Riverside, could make you believe that flower power might yet pollinate the planet, and these Bees would provide the soundtrack. It didn’t quite work out that way, but wasn’t it pretty to think so?

The King Bee in the equation, Willie Murphy, phased the band out-or they phased themselves out-in 1984, a peak year for Minnesota’s new-wave/punk scene and the rise of Prince. But Murphy’s reputation never lost its sting. More importantly, he’ll never lose his standing as a historical linchpin that bridged the racial divide in the Twin Cities, creating the kind of integrated, black-and-white group and sound in two cities that had invisible, but clearly segregated, boundaries, especially in live music venues.

As a teen, Murphy had played with the legendary Valdons, the only white guy in the African American R&B band. It was a sign of things to come.

I often wondered what a Murphy-Prince collaboration (or friendship) might have sounded and looked like. They both consciously together racial- and gender-mixed bands, and both could play in multiple genres. As multi-instrumentalists go, Murphy was on par with Prince, and his proficiency on the soundboard as a producer was also equal to Prince’s. It’s fitting that he was inducted into the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame the same year as both Prince Rogers Nelson and Bob Dylan, in 1990.

Elektra Records offered Murphy producing jobs in LA and New York, but he turned them down-not wanting to appear to be selling out to “the Man.” Perhaps those label executives got the same buzz anyone did listening to early albums Murphy produced, such as Bonnie Raitt’s eponymous 1971 debut, which featured the Bees and special guests from Chicago A. C. Reed and Junior Wells backing her, and a stand-alone collaboration in 1969 with Spider John Koerner called Running, Jumping, Standing Still. Crawdaddy, another one of the better rock rags from the sixties, called the five-star album “perhaps the only psychedelic ragtime blues album ever made.” It came out at the end of an era in which such creative innovation was the norm rather than the exception. Willie Murphy, who started playing piano at three or four, left his imaginative signature on it.

Looking back, one wonders how large or how small those Elektra offers are written on Murphy’s list of regrets. We’ll never know the records or artists he might have shaped, or how his own solo work might have evolved. Or if his proclivities for booze and drugs would have increased and preempted the Elektra assignment. But it doesn’t take much brain sap to know that the Minnesota music scene would have been absent one of its most formidable artists ever to sit at a piano, to record at a sound-board, or to lead a band. This place simply would have been unimaginable without him.

Offstage, Murphy could be friendly, charming, and irascible, sometimes all at once. Spend any time with him and you’d discover he was a devoted cinephile (sometimes seeing nearly the entire run of local film festivals) and well read, heavy on the modern Irish novelists. After delivering part of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s poem “I Am Waiting” as part of my best man duties at writer Tom Surowicz’s wedding, I was approached by Willie, who told me how much he loved the Beat poets, adding, “I just heard that same poem read at a funeral.” He was a glass is half full and glass is half empty dude.

When the Bees disbanded, Murphy went to work on a solo gig, producing the album Willie Murphy Hits Piano/Piano Hits Willie Murphy as his calling card. He put out the keeper album on his own label, Atomic Theory Records. He took a tip from the DIY principle that defined much of the eighties, as bands and recording artists realized they might not need big labels anymore, despite the daunting challenges that distribution, marketing, and promotion presented.

Atomic Theory went on to release albums by other artists, among them folkie Larry Long, acclaimed country singer Becky Thompson, reggae band Ipso Facto, the punky Irish folk band Boiled in Lead, Phil Heywood’s remarkable acoustic delight, Some Summer Day, and a blues record by legendary bluesmen Hubert Sumlin and Jimmy Rogers, with harp player Bill Hickey. There’s even a quirky world music entry from the New International Trio, which blended Cambodian folk music with bagpipes, harpsichord, and other instruments! Murphy’s tastes were universal to the core.

In 2009, the clean and sober artist issued a personalized paean to peace and better times with the double CD A Shot of Love in a Time of Need/Autobiographical Notes. This one was released by the St. Paul indie label founded by Bob Feldman, Red House Records, and it finally pushed the now-former West Banker into the Top 15 on Billboard’s blues chart. Murphy’s most recent group, the Angel Headed Hipsters, took its name from the first lines in Allen Ginsberg’s epic poem, “Howl,” and their funky direction from the long-running, long-jumping, still-standing lead musician. Murph and the Angel Heads delivered another stunning, eclectic disc late in 2018, Dirtball, in which he decried the environmental state of the planet and the divisions among people; the aging hipster had not lost sight of the hippie manifestos from his youth.

After several threats, the Bees finally reunited in 2014, for the fortieth anniversary of the Cabooze. Surviving members, longtime fans, and younger, curious music buffs all grooved to soul-stirring covers and original band classics like “Honey from the Bee”; Murphy’s put-down of excessive consumer culture, “Supermarket”; and the caustic slow burner, “You’re No Good, You’re Funky (You’re Mean and Nasty Too).”

The horn section, including Maurice Jacox-the tall black man in the Globetrotter’s uniform playing the big horn from the old days-still had their stuff, and the rhythm section kept the buzz blazing for two sets. It was a fitting victory lap for two West Bank institutions. One is still intact. The other was embodied in the man who sat down for solo gigs at places like the Richfield American Legion and proceeded to demonstrate why Willie Murphy was still the undisputed champ of rock ‘n’ roll here.

But in mid-January of 2019, at age seventy-five, the King Bee succumbed to the many medical problems that plagued him in the last year of his life. Fortunately, in November 2018, he was well enough to greet fans, old friends and lovers, and those who had helped him crowdfund Dirtball at the Eagles Club in south Minneapolis, which has become a second home to the West Bank scene. He couldn’t sing because of his health complications but still managed to fill the dance floor as the sound of his new album filled the hall. Others lined up to greet him some ten to twenty deep. “It was like kids waiting to see Santa,” quipped Max Ray, one of the Angel Headed Hipsters and a longtime friend and caregiver who was with him when he passed on. Another old friend, Tony Glover (of Koerner, Ray, and Glover), lamented his final exit off the bandstand. “Willie knew where the music was-he played with the authority to get right into the core of it. There was fun in his funkiness, and his lyrical visions were as high as his blues were low down. There’s a hole where he used to be,” the fellow bluesman said. “The Man will be missed.”

Funky angel-headed hipster ghost, come back, if only to sow your vision of harmony among the weary dancers, one more time . . .

Minnesota’s versatile multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, producer, and band leader Willie Murphy relaxes in a hammock at his West Bank home. Photo by Greg Helgeson.

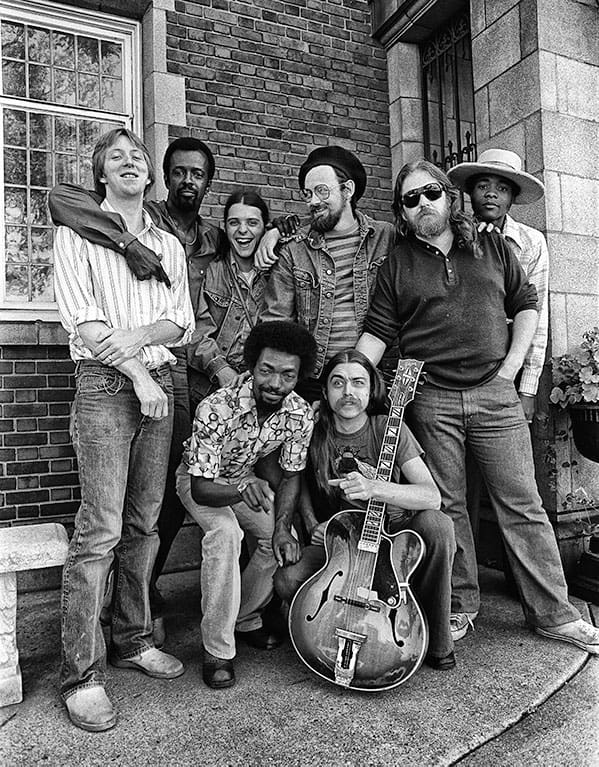

Minnesota’s versatile multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, producer, and band leader Willie Murphy relaxes in a hammock at his West Bank home. Photo by Greg Helgeson.  Willie and the Bees, nearing the height of their rock ‘n’ roll bumblebee flight in September 1979, pose in front of the old Walker Church in south Minneapolis. The church was the original site of the community radio station KFAI-FM, on the left of the dial, where Willie Murphy’s show, Jammin’ with Willie, was must-listen radio every Friday afternoon. Photo by Greg Helgeson.

Willie and the Bees, nearing the height of their rock ‘n’ roll bumblebee flight in September 1979, pose in front of the old Walker Church in south Minneapolis. The church was the original site of the community radio station KFAI-FM, on the left of the dial, where Willie Murphy’s show, Jammin’ with Willie, was must-listen radio every Friday afternoon. Photo by Greg Helgeson.