Independent Spirit

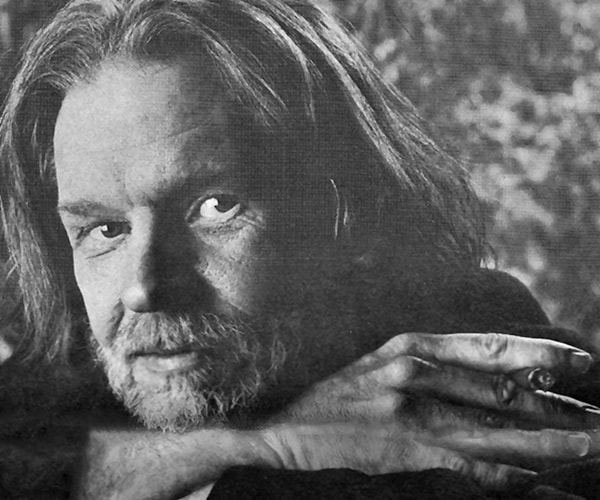

Willie Murphy will make his mark in his own way – or not at all.

IT’S A WEDNESDAY night on the West Bank in Minneapolis, and Willie Murphy is holding court at the 400 Bar–as he has on nearly every Wednesday night for the past five years.

You hear Murphy before you see him. His gravel-throated singing and the rumbling beat of his piano pounding drift out of the bar and over Cedar Avenue. The sound inside reverberates in the crowded room as Murphy’s melismatic growl bends and twists the lyrics of Roy Brown’s 1948 rhythm-and-blues hit: “Heard the news, there’s good rockin’ tonight…”

And the place is rocking – Murphy and his straight-backed chair, the battered upright piano, the scarred wooden stage, and especially the gyrating listeners crowded in front of the stage. The energy of Murphy’s playing is spellbinding as he hammers out a primitive three-chord boogie pattern with his left hand and springs up and down the keyboard with his right, throwing off improvised clusters of blue notes. As any Wednesday night wears on, Murphy flips through a dog-eared spiral notebook propped on the piano and takes his audience on an aural tour of vintage rock ‘n’ roll, back-alley Chicago blues, early Beatles, mid-Sixties Motown, even a little jazz.

The sound is larger than life – certainly larger than Murphy himself, a stocky, scraggly-haired figure crouched over the rattling keys. The setting is plain; the only stage lighting is a pair of orange-and-green neon beer signs that hang in the window. Murphy’s red-bearded face is shrouded in the shadows of the dark, smoky room.

Shadows. Despite his undeniable talents as a songwriter, performer, and arranger, Murphy has spent most of his three-decade career in the shadows. Most of the college students who come to hear him at the 400 probably don’t know that Murphy was one of the three charter members of the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame (the others: Bob Dylan and Prince) or that he has been playing music in Twin Cities nightclubs since before they were born.

Murphy came to music early–at four years old, when he sang in a children’s choir. The nuns at St. Stephen’s parish in south Minneapolis gave him his first piano lessons, and by fifth grade Murphy was teaching himself to emulate the unorthodox playing of rock ‘n’ roll pioneers Fats Domino and Jerry Lee Lewis. Murphy still remembers the first time he threw his head back and cut loose with the half-shout/half-scream popularized by Little Richard. He recreates that same near-ecstasy every time he sits down at the 400’s piano. “Music, for me, is a great emotional release”, Murphy says, during a late-afternoon lunch at one of his favorite daytime haunts, the New Riverside Cafe. “There’s something about pounding the piano and singing, and doing it full out, that’s very satisfying – especially when there are people listening who get the same feeling. The screaming and hollering… I could hardly live without it.”

Murphy spent his late teens and early twenties serving a kind of rhythm-and-blues apprenticeship, playing in a series of bar bands: the Valdons, the Nobles, the Versatiles, Dave Brady and the Stars. Those bands played whatever soul and R & B tunes were popular at the time, providing Murphy with a firsthand education in the evolution of the music. He also attended–briefly–the MacPhail School of Music, hoping to become a jazz pianist; he left, he says, because he lacked the discipline to put in the necessary practice time.

Murphy taught himself music theory enough to become a respected arranger by listening to his vast collection of jazz albums. At times, he recalls, his record player’s platter spun 20 hours a day.

Murphy earned his first national recognition “almost without trying” in 1969, when he collaborated with folk singer/songwriter John Koerner (who had gained a measure of fame himself as a member of the folk-blues trio Koerner, Ray, and Glover) to produce an eccentric but enjoyable LP for Elektra Records, Running, Jumping, Standing Still. One national rock magazine picked that album as one of the best of the decade. The Elektra contract called for a second album, but Koerner decided to retire from performing (temporarily, as it turned out) to make films. Elektra offered Murphy a job as a producer in either New York or Los Angeles; he declined. “It was the end of the Sixties, and I was still very much in the anti-establishment mode,” he says. “I still am, to some extent. I didn’t want to fool around with corporate America, and I wanted to put together a band that would play music for music’s sake.”

The band he put together, Willie and the Bumblebees, went on to achieve the status of a local institution – a favorite of critics and fellow musicians – through its inimitably earthy style and deft musicianship in a multitude of genres, including R & B, electronic “funk”, blues, rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, and reggae. The band’s repertoire relied heavily on Murphy’s original songs and complex, jazzy arrangements. Because they were a big group–as many as nine pieces, at times–and because they refused to play the Top 40 tunes that most club owners favored, the Bees lived an impoverished existence. Yet they managed to persevere through 14 years’ worth of sweat-soaked bar gigs, benefit dances, and occasional–very occasional–theater performances. During the hard times, Murphy would sometimes speculate about what might have been if he’d taken the Elektra job. “Like a lot of other people, I have a big ego,” he says. “Without articulating it at the time, I probably thought that someone would come along and discover me. But it usually doesn’t happen that way. And after the fun gets overwhelmed by some of the other realities of playing music in bars, you decide it would be nice to make a little more money at it. Of course, by that time, it’s probably too late”

Among the harsh realities in Murphy’s past was a lengthy bout with alcohol and cocaine addiction that severely damaged his health–he was hospitalized twice–before he managed to get straight in the late Seventies. “I have a lot of fond memories from that time, but… I could have quit five or even 10 years earlier than I did – and I wouldn’t have missed anything but a lot of pain.” Murphy says that his career might have blossomed more fully had he been clear-headed; on the other hand, he says, “I could have been a really big abuser in New York and burned out at an early age.” Playing music in bars doesn’t bother him, these days, since he’s lost the urge to use drugs: “I know it’s not as exciting to be in those places as you think it is when you’re loaded.”

In 1984, having established his solo piano gig at the 400 Bar, Murphy decided to disband the Bees and pursue other musical ambitions. He managed to finance the purchase of 12-track recording equipment and to set up a studio in his West Bank home. He and a friend named Elka Malkis also established a record label, Atomic Theory. Their first release, Willie Murphy Piano Hits/Willie Murphy Hits Piano, sold enough copies locally to finance a follow-up, which Murphy hopes to finish this year.

These days, Murphy spends most of his time working on a variety of recording projects at home and in other local studios. One is an LP by a West Bank instrumental group called the New International Trio: an elderly Cambodian immigrant and two classically trained Americans, who play traditional and modern music from England, France, Finland, and Cambodia (not to mention a bit of American jazz)

Murphy has also been working on a record by local country singer Becky Reimer Thompson (which was slated for a January release) and one by composer/singer/violinist Wendy Ultan. Another project in the offing–a cassette recording–would find Murphy providing musical backing for local poet Roy McBride.

But the project Murphy is proudest of is a forthcoming album of his own songs a recording on which he plays most of the instruments, including guitar, keyboards, bass, and drum machine. Two prominent friends helped out: singer Bonnie Raitt, who added backup vocals, and multi-instrumentalist Steve Tibbetts, who is internationally known for his records on the German ECM jazz label.

Murphy has long been a prolific songwriter, with a knack for moody, introspective themes. He says that the new album offers a better setting for that sort of material than did the Bumblebees, whose repertoire emphasized the danceable blues and funk tunes that bar-goers love. The new songs touch on midlife issues of dreams and fleeting time, and on some political topics.

As he nears his mid-forties, Murphy is acutely aware of the irony of his situation. Any sign of bitterness at his lack of commercial success is masked by his well-honed sense of sardonic humor “I’m not a has-been, because I haven’t made it yet” he says. “That’s a nice way to look at it. I’ve heard people in the local record industry call some bands ‘too old’ because they’re over 30. Here I am, over 40, and putting out a rock ‘n’ roll record, and I’ll probably have to start another band to play that music. People have asked me if I shouldn’t quit. But music is what I chose to do with my life.”

Today’s multitrack technology makes it easier for an independent soul such as Murphy to fulfill his long-standing ambition of making his own records–but ensuring that those records will find an audience remains an uphill trek. It is still a fact of life that record sales are primarily a function of restrictive radio-station playlists and the buying decisions of larger record-store chains. As a result, Murphy says, the marketplace continues to discourage creativity and reward imitation: “Selling records is still really a big racket. There are so many middlemen that it’s hard to get any distribution. We’re not trying to compete directly with the large record companies. But in terms of getting records in the stores, the big hit records on the big labels are the stores’ first priorities – which puts the small independents at the bottom of the totem pole. And even when stores will stock your records, they might not pay you. When they have to meet the nut, the Billy Joels and Bruce Springsteens get paid first.”

There are those who have succeeded in the commercial mainstream who say that Murphy still has the talent to “make it,” with a little luck. Minneapolis-based producer David Rivkin, who is nationally known for his work with million-selling artists such as Prince and the Jets, calls Murphy “a great, undiscovered talent who hasn’t attained the success he deserved. It’s a matter of time and place, I guess.” (Rivkin recently employed Murphy as a songwriter and arranger for singer Germaine Brooks.) Bob Feldman of St. Paul who founded the successful Red House record label, says that in the popular music marketplace, Murphy is a misfit–in the most complimentary sense of the word. “I don’t think the music industry has often been able to communicate anything as honest and all-encompassing as Willie’s music to a mass audience. We’re lucky to have a person like him in our midst.”

Murphy, the diehard iconoclast, says he is ready for success – but only on his own terms. “Music is a very personal thing. If people understand and appreciate my music, that’s very nice. But if they don’t, I won’t worry about it.”